COMPASS TO THE COSMOS / ISAEL ANDRADE

Across cultures and millennia, people have looked to the night sky for direction. Among the stars, one has remained constant. In Hindi, it is called Druva, “the Fixed One.” In Lakota, it is called Wičháȟpi Owáŋžila, the “Star That Sits Still.” In Plains Cree, it is called acâhkos êkâ kâ-âhcît, the “Star That Does Not Move.” In ancient Finnish, it is called Taivaannaula, the “Nail in the Sky.” In Old English, it is called Scip-Steorra, the “Ship Star.” In modern English, it is called Polaris, the “North Star.”

Its place near the Earth’s rotational axis gives the North Star a unique quality: it appears motionless while the rest of the sky rotates around it. For thousands of years, sailors and travelers from civilizations such as the Greeks, Phoenicians, Egyptians, and Polynesians used it to orient themselves across land and sea. When nothing else was fixed, the North Star was a constant, guiding people through darkness, uncertainty, and uncharted territory.

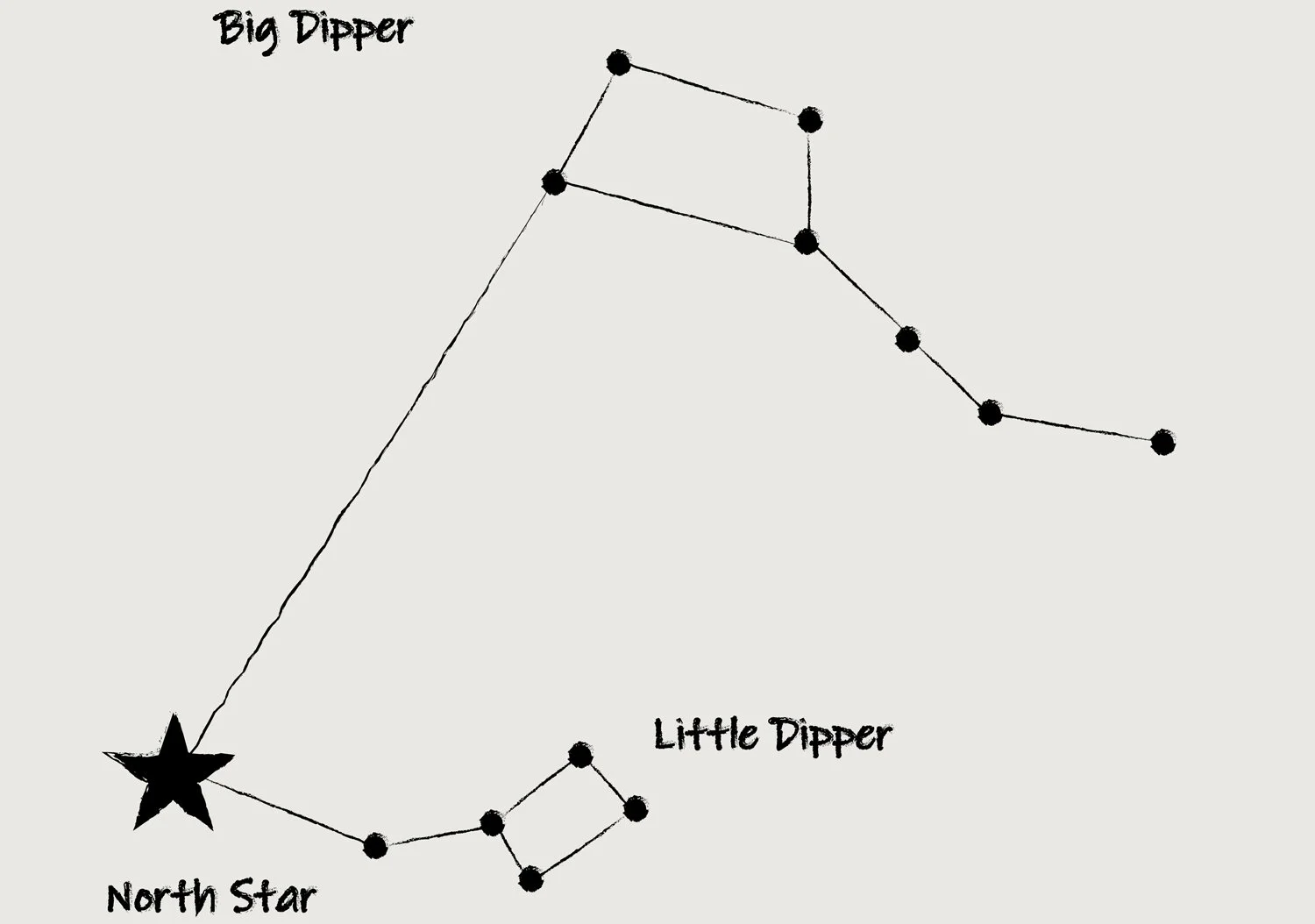

In the United States, the North Star took on new meaning during the era of slavery. Enslaved people escaping bondage often fled north under the cover of night, using the star to navigate toward freedom. Many aimed for Canada, beyond the reach of traffickers in human bondage and U.S. law. The Big Dipper, shaped like a ladle or gourd, a prominent asterism visible in spring skies, served as a pointer to the North Star. Without maps or compasses, those in flight watched the sky, trusting the North Star to carry them to safety.

The North Star can be found by tracing a line from the Big Dipper to the Little Dipper.

But the star was more than a navigational tool, it became a symbol of possibility. As the following examples show, it was embraced by the black intellectual and political class in the mid-nineteenth century as a metaphor for hope, clarity, and self-direction.

Frederick Douglass named his 1847 newspaper The North Star, cementing its status in African American political thought. In the paper’s first issue, he wrote, “To millions, now in our boasted land of liberty, it is the STAR OF HOPE.” His words positioned the star as a literal and spiritual guide for those seeking lives beyond the reach of enslavers.1

Henry Bibb, in his 1849 Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave, recounted using the stars to flee enslavement: “I walked with bold courage, trusting in the arm of Omnipotence; guided by the unchangeable North Star by night…” For Bibb, the North Star was both compass and prayer, orienting his steps as he moved toward liberation.2

William J. Wilson, writing under the pen name Ethiop, envisioned an imagined African American museum in his 1859 essay “Afric-American Picture Gallery.” In a pair of artworks titled The Underground Railroad, he paints a nighttime forest where the North Star gleams “small but bright and unfailing, and to the fugitive, unerring.” In Wilson’s hands, the star becomes art—its light illuminating the path of generations in search of deliverance.3

William Still’s 1872 Underground Railroad contains similar references to the North Star, emphasizing its role as a symbol of vision and resolve for freedom seekers. As a prominent abolitionist and historian, Still documented the firsthand accounts of formerly enslaved people who navigated the perilous journey to North. In one account, he describes Alfred, an escapee from Virginia who, despite facing relentless rain and adverse weather, remained determined to reach free soil: “But the North Star, as it were, hid its face from him. For a week he was trying to reach free soil, the rain scarcely ceasing for an hour.” The star’s absence in this passage is as powerful as its presence—its light longed for, its guidance withheld, but never forgotten.4

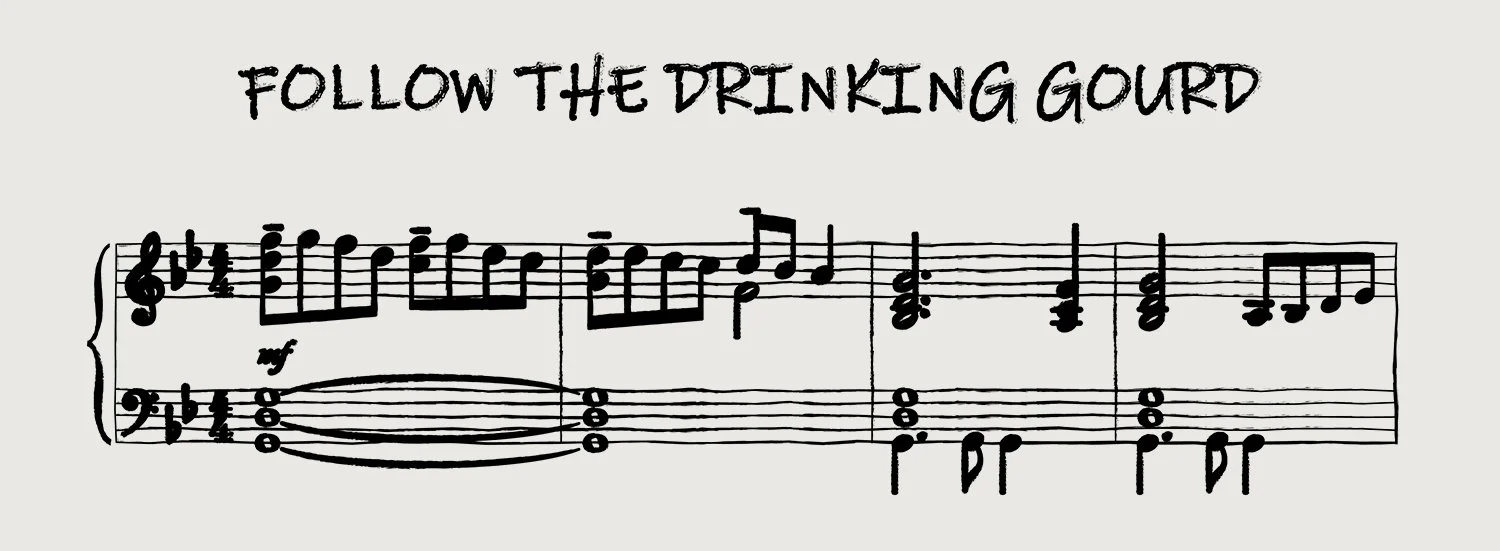

Even in postbellum memory, the North Star retained its meaning. Though written decades after slavery’s end, the folk song “Follow the Drinking Gourd” preserved the oral traditions of formerly enslaved people. In it, the Big Dipper’s handle—shaped like a gourd—leads to the North Star, which in turn leads to freedom. The song is both map and memory, sung across generations.

“Follow the Drinking Gourd” refers to the Big Dipper, whose stars point to Polaris, the North Star. In song and story, it became a coded instruction: look to the sky, find the star, and move north.

The North Star remains one of the most enduring symbols in African American history—a fixed light that guided people through physical and spiritual darkness. It represents orientation, resilience, and the right to choose one’s path. North Star draws inspiration from this legacy. Through fashion, we tell stories rooted in the histories of the African Diaspora—stories of survival, creativity, and reclamation. We use textiles not just to clothe the body, but to chart a new direction. Like the North Star, we aim to be a constant—illuminating the past while guiding toward a freer future.

Follow our direction. Find your North Star.

1. Frederick Douglass, “Our Paper and Its Prospects,” The North Star (Rochester, NY), December 3, 1847,

https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn84026365/1847-12-03/ed-1/?sp=2&r=-1.335,-0.018,3.669,1.546,0.

2. Henry Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb, an American Slave, Written by Himself (New York: Published by the Author, 1849), 51.

3. William J. Wilson (Ethiop), “Afric-American Picture Gallery,” The Anglo-African Magazine 1 (January 1859), 54.

4. William Still, The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c., Narrating the Hardships, Hair-Breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in Their Efforts for Freedom (Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1872), 171.